When HIV first enters your body, it doesn’t just float around-it hijacks your cells and starts copying itself nonstop. One of the drugs built to stop that process is nevirapine. It’s not a cure, but since the 1990s, it’s been a key player in keeping HIV from taking over. If you’ve ever wondered how a single pill can slow down a virus that mutates faster than most drugs can keep up, the answer lies in how nevirapine jams the virus’s internal machinery.

How HIV Copies Itself-And Why That’s a Problem

HIV is a retrovirus. That means it carries its genetic code in RNA, not DNA like human cells. To turn itself into a permanent part of your body, it needs to convert its RNA into DNA. That’s where an enzyme called reverse transcriptase comes in. Think of it as a photocopy machine made for viruses. Without it, HIV can’t replicate. But this machine is sloppy. It makes mistakes-about one error every 10,000 letters. That’s why HIV has so many versions, or strains. It’s also why drugs need to be precise.

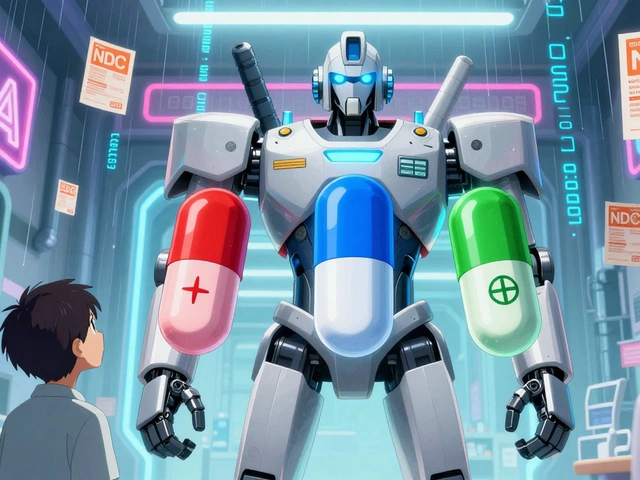

Most antiviral drugs try to trick the reverse transcriptase machine by feeding it fake building blocks. Nevirapine does something different. It doesn’t pretend to be a DNA piece. Instead, it latches onto the enzyme itself and locks it in place.

Nevirapine’s Unique Mechanism: The Allosteric Lock

Nevirapine is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, or NNRTI. That long name means it binds to a spot on the reverse transcriptase enzyme that’s not where the actual DNA building blocks go. This is called an allosteric site. When nevirapine sticks there, it changes the shape of the enzyme like bending a key so it no longer fits in a lock.

The enzyme still tries to work, but it can’t hold the RNA and DNA strands properly. It stumbles. It slows down. Eventually, it stops. No DNA copy means no new virus particles. That’s how nevirapine stops HIV from spreading inside your body.

Unlike nucleoside inhibitors, which get incorporated into the growing DNA chain and cause early termination, nevirapine doesn’t get used at all. It’s more like a wrench thrown into the gears. This makes it useful in combination with other drugs that work differently.

Why Nevirapine Is Used in Combination Therapy

Using nevirapine alone sounds like a good idea-until you realize how fast HIV mutates. In a single patient, dozens of viral variants can appear in weeks. If even one has a mutation that changes the shape of the reverse transcriptase enzyme just a little, nevirapine won’t bind to it anymore. That one mutant survives, multiplies, and becomes the new dominant strain.

That’s why nevirapine is never used alone. It’s always part of a combo-usually two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (like tenofovir and emtricitabine) plus nevirapine. This is called triple therapy or ART (antiretroviral therapy). Each drug hits a different target. Even if one drug fails, the others still hold the virus back.

Studies from the early 2000s showed that patients on nevirapine-based regimens had a 70-80% drop in viral load after 24 weeks. But those results dropped sharply if doses were missed. Consistency matters more with nevirapine than with some newer drugs.

Who Gets Nevirapine Today?

Nevirapine isn’t the first choice for new patients in the U.S. or Europe anymore. Drugs like dolutegravir and bictegravir are more potent, have fewer side effects, and don’t require dose escalation. But nevirapine is still widely used in low- and middle-income countries.

Why? It’s cheap. A month’s supply costs under $10 in some regions. It’s stable at room temperature. It doesn’t need refrigeration. And it’s been used for decades, so doctors know how to manage it. In sub-Saharan Africa, it’s still a backbone of prevention programs-especially for stopping mother-to-child transmission during childbirth.

In fact, a single dose of nevirapine given to a mother during labor and another to the newborn within 72 hours cuts transmission risk by about 50%. That’s why the WHO still lists it as an essential medicine.

Side Effects and Risks: The Trade-Off

Nevirapine isn’t without risks. About 1 in 10 people develop a rash in the first few weeks. Most are mild, but 1-2% develop severe skin reactions like Stevens-Johnson syndrome. That’s why doctors start with a low dose for the first two weeks-called lead-in dosing-to give the body time to adjust.

Liver toxicity is another concern. About 5% of patients show elevated liver enzymes. The risk is higher in women with CD4 counts over 250 and in men with counts over 400. That’s why blood tests are required before and during treatment.

Because of these risks, nevirapine isn’t recommended for people with pre-existing liver disease or hepatitis B or C. It also interacts with many other drugs, including some TB medications and hormonal birth control. That’s why treatment plans need to be personalized.

What Happens If Nevirapine Stops Working?

Resistance to nevirapine develops quickly-sometimes after just one missed dose. The most common mutation is K103N. That single change in the reverse transcriptase gene makes the enzyme’s shape just different enough that nevirapine can’t grip it anymore.

Once that mutation is present, nevirapine won’t work again, even if you restart it later. That’s why resistance testing is recommended before starting any NNRTI-based regimen. If resistance is already there, doctors switch to a different class of drugs, like integrase inhibitors.

But here’s the thing: even if nevirapine fails, it doesn’t mean the whole treatment fails. Other drugs in the combo still work. And newer drugs can be added without starting from scratch.

The Bigger Picture: Why Nevirapine Still Matters

Nevirapine isn’t glamorous. It doesn’t have the lowest side effect profile or the highest barrier to resistance. But it’s one of the most cost-effective tools we’ve ever had against HIV. It helped turn a death sentence into a manageable condition for millions. In places where access to medicine is limited, it’s still the difference between life and death.

Its science is simple but brilliant: don’t fight the virus head-on. Jam its tools. Break its rhythm. Let other drugs handle the rest. That’s the power of combination therapy-and why nevirapine, despite its age, still has a place in global health.

Is nevirapine still used to treat HIV today?

Yes, but mostly in low- and middle-income countries where cost and availability matter more than cutting-edge options. In high-income countries, it’s rarely a first choice due to newer, safer drugs. However, it’s still used for preventing mother-to-child transmission during childbirth.

How does nevirapine differ from other HIV drugs?

Nevirapine is an NNRTI-it binds to a specific spot on the HIV reverse transcriptase enzyme and changes its shape, making it useless. Most other drugs, like tenofovir, are nucleoside analogs that trick the enzyme into using fake building blocks. Nevirapine doesn’t get incorporated; it just disables the machine.

Can you take nevirapine alone for HIV?

No. Taking nevirapine alone leads to rapid drug resistance. HIV mutates too quickly. It’s always used in combination with at least two other antiretroviral drugs to suppress the virus effectively and prevent resistance.

What are the biggest side effects of nevirapine?

The most serious side effects are severe skin rashes and liver damage. About 1-2% of users develop life-threatening skin reactions, and 5% show signs of liver stress. These risks are highest in the first 6-12 weeks, which is why doctors start with a low dose and monitor liver enzymes closely.

Does nevirapine work against all strains of HIV?

No. Some HIV strains already carry mutations-like K103N-that make nevirapine ineffective before treatment even starts. That’s why resistance testing is important before prescribing it. Even if the strain is sensitive at first, missing doses can quickly lead to resistance.

Why is nevirapine still on the WHO’s Essential Medicines List?

Because it’s affordable, stable without refrigeration, and proven effective at preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission. In resource-limited settings, it saves lives even if it’s not the most advanced option. Its role in public health outweighs its limitations.

Post A Comment